Inside the Violin Workshop in Nice: Where Craft Meets Music

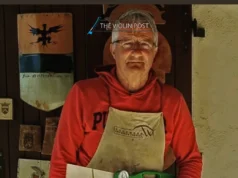

Amid the aromatic blend of turpentine, spruce bark, rosin, and linseed oil, lies Du Bois à la Musique, a violin workshop located in the French city of Nice. Here, luthiers Joffrey Waltz and Anne Gouriano dedicate their expertise to repairing and crafting violin family instruments, helping musicians achieve their finest performances.

“How would you define the smell of a violin-making workshop?” Joffrey Waltz asks his colleague Anne Gouriano as she works on a double bass across the space. “Unique,” she responds with a laugh, capturing the distinctive atmosphere that defines this workshop.

Waltz and Gouriano acquired the workshop in 2017, taking over from the previous owner and violin maker, Pierre Allain. Waltz explains his role: “My job is to adapt a piece of wood to an instrument and make the most of it,” highlighting the intricate nature of lutherie.

Becoming a luthier requires extensive training—typically three to four years before even being considered a beginner. Waltz notes the necessity of skill and precision when handling valuable instruments, often worth five or six figures.

Inside the workshop, violins occupy numerous shelves, many awaiting restoration and bearing identifying labels, while others are ready for collection by their owners. Gouriano shares insights into their workflow, saying, “The most dangerous jobs are when people do not give a set date, and just say ‘whenever you can.’ I usually get concerned then because they’re the ones who call a few days later asking for progress updates.”

Focus on Repair and Custom Making

The majority of their work—approximately 95%—involves repairing stringed instruments such as violins and cellos. These repairs address issues stemming from accidents, normal wear and tear, or climate-induced damage.

The remaining 5% involves crafting bespoke instruments tailored to professional musicians’ individual playing styles, emphasizing the personalized nature of their craft.

“Planing is what we do mostly,” Waltz explains, referring to the process of finely shaving down worn-down fingerboards. One recent repair involved a violin owned by a gentleman who developed an interest in the instrument after his daughter started playing.

Tools of the Trade and Unique Instruments

Waltz’s desk is backed by a collection of specialized tools mounted on the walls. Among these are “canifs,” a variety of knives designed for precision work in the most confined spaces of the instrument. For example, the canif à chevalet is skillfully used to shape the curves of F-holes. Additionally, a slender rod called a pointe aux âmes is specifically made for adjusting the sound post inside violins, a critical wooden piece that influences the instrument’s characteristic tone and, poetically, is known as the instrument’s âme or soul.

From Musical Beginnings to Master Craftsmanship

Waltz’s passion for violin making was sparked by playing the cello from the age of eight. He graduated from the renowned Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume school in Mirecourt, a town famed for string instrument production since the 1600s. His experience further expanded at Bernard Sabatier’s violin shop in Paris, located on the celebrated Rue de Rome, a historic hub for luthiers.

Similarly, Gouriano began studying violin, viola, and harp at six years old and trained at the Ecole Internationale de Lutherie Jean-Jacques Pagès, also in Mirecourt. She gained professional experience in Paris at Atelier Charton. Both luthiers completed internships at Allain et Gasq Luthier Archetier, the workshop which they ultimately purchased.

Though playing a stringed instrument is not mandatory to become a luthier, Waltz emphasizes its importance for better understanding musicians’ perspectives and requirements. He jokes that all violin makers should receive psychology training because managing relationships with professional musicians—often demanding clients—can be challenging.

Cultural Expressions and the Luthier’s Connection to Music

Both Waltz and Gouriano not only play string instruments but also often reflect on idiomatic expressions related to the violin. For instance, the French phrase “le violon d’Ingres,” referring to a hobby, draws from the neoclassical painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, who played violin alongside his artistic work.

More colorful is the French expression “pisser dans un violon” which translates to “peeing in a violin,” used to describe a futile or pointless activity. Historically dating back to 1860, the phrase evolved from “souffler dans un violon” (blowing into a violin) – an absurd attempt to produce wind-like sounds from a string instrument.

Waltz chuckles, completing the thought: “It’s completely useless.”

— The Violin Post Editorial Staff