While driving through Westlake to visit Nathaniel Anthony Ayers at his nursing home, I suddenly realized it had been 20 years since we first met.

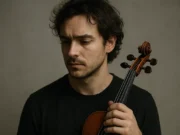

That meeting happened around noon on a drizzly late-winter day in 2005. I heard violin music in Pershing Square and followed the sound to find Mr. Ayers next to a shopping cart piled high with his belongings.

Mr. Ayers was holding a violin missing two strings, striving to reconnect with his musical roots nearly thirty years after illness forced him to leave the prestigious Juilliard School in New York. I had my notebook, ready to learn about this Cleveland-born prodigy while trying to understand the mental health system that left many people like him stranded on the streets of Los Angeles.

Neither of us could have predicted the journey ahead that would take us to unforgettable places like Disney Hall, the Hollywood Bowl, Dodger Stadium, the beach, and even the White House. Our story unfolded with moments of both harmony and hardship, guided by what Mr. Ayers calls “the music of the gods.”

During my recent visit, I remarked, “Can you believe we’ve been friends for 20 years?” Immobilized by a hip injury, Mr. Ayers looked up, surprised, then smiled, reflecting that at our meeting he was homeless, playing a violin with just two strings.

The first column I wrote about him was headlined “Violinist has the world on 2 strings,” capturing his unyielding passion for music despite his circumstances. He played near the Beethoven statue in Pershing Square for inspiration, and his shopping cart bore a sign that read “Little Walt Disney Concert Hall.”

Following the column’s publication, six readers donated violins, two others contributed cellos, and another gifted a piano. We transported the piano to a music room in Skid Row, established at a homeless services agency now called The People Concern, with Mr. Ayers’ name on the door.

It took a year to persuade him to move indoors. Throughout that time, he taught me that every individual experiencing homelessness and mental illness has unique fears, needs, and a complex history of trauma and stigmatization. Many struggle within a fragmented, multiagency care system.

Through Mr. Ayers, I encountered numerous dedicated public servants in the mental health field, who work tirelessly to offer comfort and change lives despite immense challenges. The growing issue of street drugs used for self-medication complicates treatment, and despite billions spent on solutions, progress is often hindered.

Jon Sherin, former chief of the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health, acknowledged the good work done but noted that bureaucracy frequently stifles innovation and demoralizes frontline workers. He stated, “We live in a world in which people are paid to deliver a service regardless of whether it has any impact, and billing becomes the primary agenda of the bureaucracy and everybody in it. We’re taking care of process and not outcomes.” Sherin advocates for adequate resources for housing and support, emphasizing safe living environments anchored by “the three Ps—people, place, and purpose.”

Over the past two decades, many individuals have invested time and care in supporting Mr. Ayers, often facing both heartbreak and hope. His sister Jennifer acts as his conservator, longtime family friend Bobby Witbeck regularly checks on him, and Juilliard classmate Joe Russo remains involved. Gary Foster, producer of the film “The Soloist”—based on my book about Mr. Ayers—has served on The People Concern’s board, supporting him along with others.

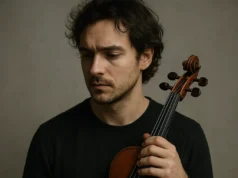

In 2005, Peter Snyder, then a cellist for the L.A. Philharmonic, began giving Mr. Ayers music lessons at an apartment where he would eventually live. Adam Crane, formerly with L.A. Phil communications and now at the New York Philharmonic, helped bring Mr. Ayers into the Disney Hall community of musicians. Pianist Joanne Pearce Martin, cellist Ben Hong, violinist Vijay Gupta, and others befriended and played music with him.

One memorable evening at Disney Hall, Mr. Ayers reunited backstage with the eminent cellist Yo-Yo Ma after a concert. Crane shared, “Nathaniel has had an astounding, life-changing impact on me. I’ve often spoken about music’s transformative power, but the time with Nathaniel has shown me this in the deepest, most passionate way. From when I first met him playing my cello in 2005 to his years on and off the streets, his love and dependence on music remained constant.”

Crane added there was an immediate, profound connection not only due to their shared love of music but also their personal struggles with mental illness. Mr. Ayers influenced Crane’s understanding of mental health and the human experience, enriching his appreciation of music’s significance.

A recent visit with Mr. Ayers included Anthony Ruffin, a former social worker who lost his home in the January Altadena fire. Despite periods of resistance and occasional hostility—Mr. Ayers once “fired” Ruffin and his mentor Mollie Lowery—Ruffin recognized the resilience beneath the surface. He said, “When I meet Nathaniel, it makes the world seem perfect. His insights on life humble me deeply.”

Years of homelessness have taken a physical toll on Mr. Ayers. Recently, injuries to his hip and hands have prevented him from playing his violin, cello, keyboard, double bass, and trumpet.

Reflecting on the past 20 years, Mr. Ayers summed it up simply and cheerfully: “Good.” We reminisced about performing at the White House for the 20th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act and meeting then-President Obama. We recalled his reunion with Yo-Yo Ma, who embraced him as a brother in music.

I remember nights from our early years together, like when he refused to leave my car until the final note of Sibelius’ Symphony No. 2 faded on the radio. Or when he shared memories of practicing Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings while watching snow fall in his New York apartment. I recall a night on Skid Row when, before sleeping, he held two sticks labeled Beethoven and Brahms, claiming a tap would scare away rats rising from the sewers.

Over two decades, Mr. Ayers has taught me patience, perseverance, humility, loyalty, and love. He reminds me that beyond first impressions and stereotypes exists shared humanity and grace, awaiting those willing to embrace it.

When I asked Mr. Ayers how he manages to endure despite hardships and setbacks, he pointed to the classical music station KUSC 91.5 FM, permanently tuned on a radio beside his bed. “Listen to the music,” he advised.

Steve Lopez

steve.lopez@latimes.com

— The Violin Post Editorial Staff