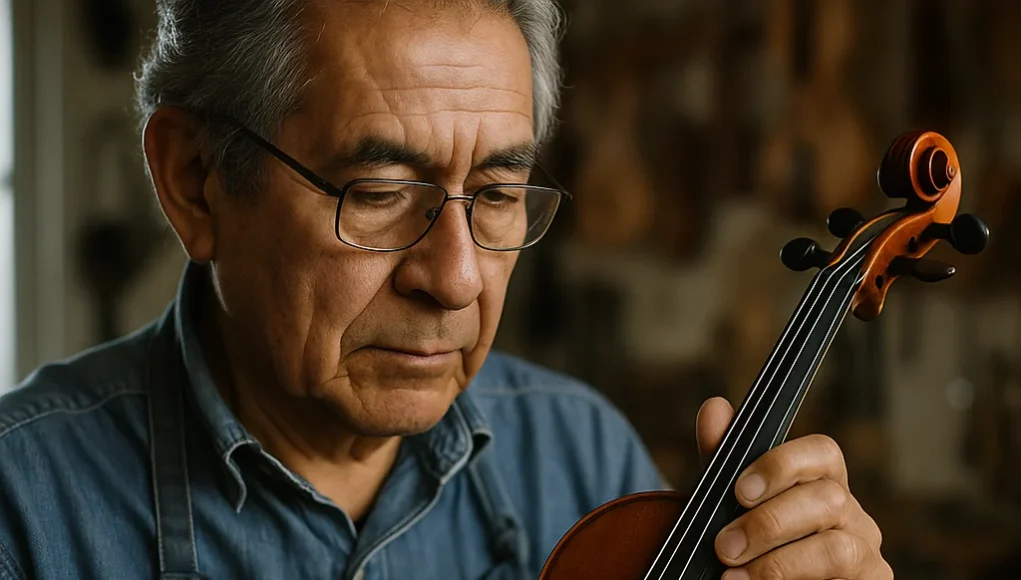

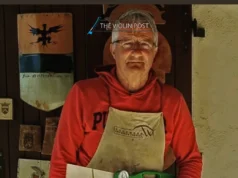

In a quaint workshop nestled in downtown Colorado Springs, Juan Mijares practices the delicate art of violin making, turning aged wood into instruments designed to resonate for centuries.

With almost four decades of experience, Mijares has become a master luthier—an artisan skilled in crafting string instruments by hand. His violins, violas, and cellos attract musicians who frequently praise their exceptional sound as “magical.”

Mijares’ journey began simply during his high school years. As he recalls, “I wanted a nice guitar and no one was going to buy me one, so I decided to figure out how to make one myself.” This curiosity led to his formal education at the Violin Making School of America in Salt Lake City, where he studied under esteemed German craftsman Peter Prier, setting the course for his lifelong vocation.

“When I come to work every day, it doesn’t feel like work,” Mijares explained. “I look forward to working on my projects, making repairs, meeting people, and selling instruments. I truly enjoy it all.”

Creating these instruments demands immense patience and skill. A single violin requires approximately 300 hours of careful workmanship, while a cello can take up to 600 hours. The materials are vital; he uses maple and spruce wood aged for ten years or more, which becomes lighter and stronger as it loses sap and volatile oils.

“The sides are carefully bent using heat and a bit of water,” Mijares described. “The top and back plates are carved from solid wood and shaped into arches before being hollowed out, much like carving a pumpkin.”

Each violin consists of roughly a hundred separate parts, joined using traditional hide glue. The precise thickness and shape of these components influence the instrument’s ultimate tonal qualities. “Measurements are often down to tenths of a millimeter,” he added.

Local musicians value having such a skilled craftsman nearby. Martha Muehleisen, a University of Colorado Colorado Springs lecturer and professional violinist, expressed relief at finding Mijares locally: “When we moved here, I was concerned about finding someone because traveling to Denver would have been difficult. Having him just 15 minutes from my home is wonderful.”

Ingrid Rodgers, a professional violist, described Mijares as a “treasure,” emphasizing how personal choosing the right instrument can be. “It’s like finding a partner. You meet many, but then you find that one special connection. That’s how it is with instruments.”

Witnessing these musician-instrument relationships develop is one of Mijares’ greatest joys. “There’s something beautiful and magical when a player picks up an instrument, connects with it, and expresses their feelings through the music,” he said.

Mijares’ handcrafted instruments range in price from $12,000 to $20,000 and are played by musicians worldwide, from Ireland to California. Some of his most cherished creations remain local—such as the instruments he has made for his own family. His youngest daughter, Sophia, recently received a custom-made cello, continuing their musical heritage.

“Every instrument is unique,” Sophia shared. “Being able to give input on how I wanted the cello was really special.”

Muehleisen highlighted the deeper connection that handcrafted instruments foster: “Knowing that an instrument was crafted with care, love, and expert skill over time creates a profound bond.”

For Mijares, the ultimate fulfillment comes from crafting instruments that endure through centuries. “The finest violins alive today are about 300 years old,” he reflected. “Building something from wood that lasts and remains useful for three centuries is extraordinary. Leaving that legacy means a lot to me.”

In today’s world of mass production, Juan Mijares represents a dwindling breed of artisans who create not just musical instruments but heirlooms destined to carry their sound across generations. As he put it, “What else lasts 300 years and just gets better?”

— The Violin Post Editorial Staff