The baryton is among the most peculiar stringed instruments ever crafted. It features gently sloped shoulders and is held between the musician’s knees like a cello, but is noticeably smaller and boasts a significantly greater number of strings. This Baroque viol relative is distinguished by an additional set of sympathetic strings located along the back of its broad fretboard, which resonate in harmony with the bowed strings in front. Designed for ambidextrous playing, musicians use their left thumb to pluck these extra strings while simultaneously fingering the fingerboard with the other fingers of their left hand and bowing with the right.

Predominantly flourishing in 17th and 18th century Europe, the baryton owes much of its repertoire to the works of Joseph Haydn. His baryton trios highlight the instrument’s gentle, delicate tone alongside cello and viola, epitomizing the refinement of classical chamber music. Baroque-era compositions demonstrate the baryton’s dual function as both melodic instrument and accompanist, with bowed melodies layered over plucked notes, reminiscent of a sparse interplay between viol and lute or harpsichord.

However, the baryton’s challenging technique and complex construction contributed to its eventual decline in popularity. It requires more intricate tuning and manufacturing than other string instruments, making it a demanding choice for musicians and makers alike. Despite this, the instrument has not vanished; it retains devoted followers ranging from amateur enthusiasts to specialized ensembles like the Valencia Baryton Project, which also commissions new baryton compositions in the modern era. A key obstacle to wider adoption remains the difficulty of procuring such a niche instrument.

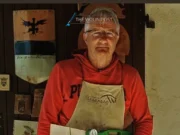

The baryton is not available commercially and requires commissioning from specialized luthiers who must blend artistry, technical skill, and historical research to recreate these rarely made instruments. English craftsman Owen Morse-Brown is one such luthier, focusing on bowed instruments from the Renaissance and Baroque periods.

Reflecting on his career, Morse-Brown shares, “I grew up playing early music and developed woodworking skills in my father’s workshop. I began building instruments as a teenager and honed my craft through both practice and formal study.” His work aligns with historically informed performance practices and demands imagination combined with investigative research. Questions such as what a baryton originally sounded like, and insights into the lives of those who built and played them, drive his dedication.

Morse-Brown emphasizes the importance of the social context surrounding these instruments. “Luthiers in the past inherited extensive hands-on knowledge often never documented,” he explains. This expertise endures for popular instruments like the violin but has largely been lost for more obscure types like the baryton, leaving modern makers to reconstruct techniques from scratch.

When undertaking commissions, Morse-Brown begins with meticulous research, examining museum collections and studying the limited surviving texts. Yet, for instruments predating 1700, “there are no existing detailed plans or instructions,” he notes.

Complicating this process is the lack of perfectly preserved originals. Gut strings wear out, wood deteriorates, and centuries of use, repairs, and environmental exposure compromise authenticity. Thus, reconstructing original designs involves educated conjecture. Earlier periods, such as the Renaissance, require reliance on iconography like church carvings and woodcuts for clues.

Morse-Brown’s barytons often feature elaborate ornamentation reflective of the Baroque era’s aesthetic, including intricately inlaid fingerboards and carved scrolls adorned with animal and human motifs. This aligns with both the period style and the expectations of his clientele, who commission these exceptional instruments as functional art.

These decorative elements also stem from the nature of surviving examples. The most ornate instruments have tended to survive through history, while simpler, more utilitarian barytons have mostly been lost.

In terms of materials, Morse-Brown selects woods similar to those used in violin making, sourcing from the same suppliers when possible. He also values using local woods to echo historical practices, which can add unique tonal variation. Fruitwoods such as pear, cherry, and plum are occasional choices. He even sometimes personally seasons wood from trees felled nearby.

The baryton’s construction follows typical bowed string instrument practices, with hardwood used for the back and sides and softwood for the soundboard. Its six or seven main strings are generally tuned like those of a bass viol, while its sympathetic strings at the back are tuned to a D major scale, complementing the majority of classical baryton compositions. This tuning arrangement produces a subtle resonance that effectively acts as natural reverberation.

Building a baryton is a complex endeavor, even for skilled luthiers. Aside from the scarcity of originals, the instrument’s numerous strings—sometimes up to 22—create immense tension inside, occasionally necessitating reinforcement bars along the neck in historical models. The double-sided string configuration demands precise neck angle calculations to prevent the strings from touching undesired parts of the instrument.

Final assembly requires meticulous care. Unlike violins or cellos, where four strings rest on a single bridge, the baryton’s raised fingerboard creates space for the sympathetic strings to pass inside a hollow neck chamber. The resonating strings extend over the instrument’s flat top, each supported by individual bridges glued by hand. This delicate process carries risks of string breakage or damage to the instrument.

“It’s a highly involved process,” Morse-Brown acknowledges. “One Baroque baryton I made had 16 plucked and 6 bowed strings. Playing it after all that work was a truly emotional experience.”

The baryton’s survival into the present owes much to composer Joseph Haydn and his patron, Prince Nikolaus I of Hungary. An extravagant aristocrat, Prince Nikolaus commissioned over a hundred works for the baryton during Haydn’s 30-year period as director of the Esterházy court orchestra.

This sustained patronage enabled Haydn’s development into a celebrated composer but also dictated his creative output. The Prince himself was a dedicated baryton player, often performing trios with friends or musicians of the court. Today, these Haydn baryton trios comprise the bulk of the instrument’s classical repertoire.

Even during its peak, the baryton was not a mainstream instrument. Morse-Brown characterizes it as “a player’s instrument,” noting that its sympathetic string resonance is subtle and mainly audible to the performer. This aligns with its role as a private luxury favored by an aristocratic patron

Haydn’s compositions for baryton skillfully accommodate the physical challenges of simultaneous bowing, plucking, and fingering. “Many pieces cleverly separate these actions,” Morse-Brown explains. “Players alternate between bowing and plucking rather than attempting both at once, making the technique demanding but manageable.”

Discover more about Baroque music in our upcoming event listings.

— The Violin Post Editorial Staff