Tradition, material, and resistance to uniformity

Introduction

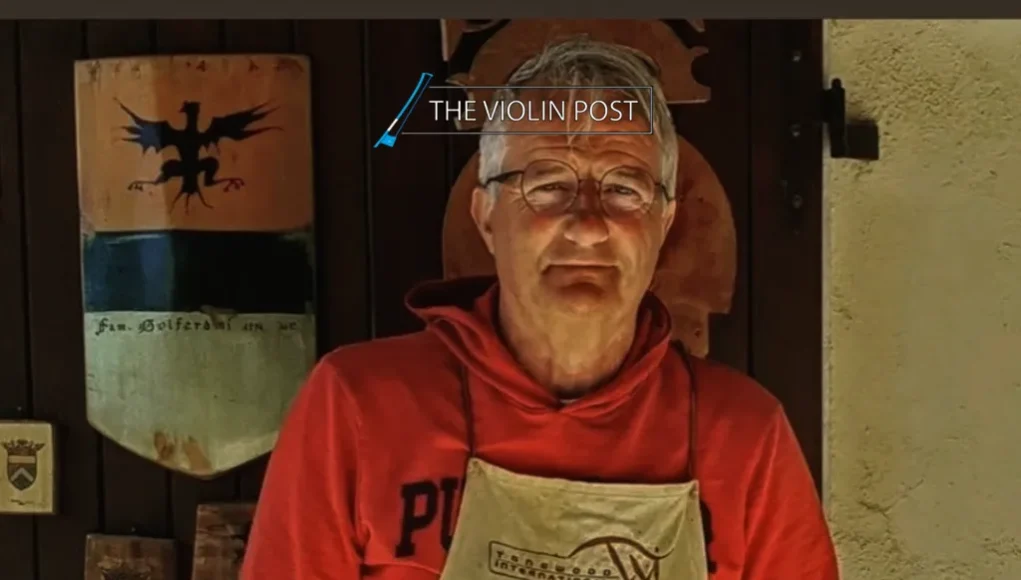

Bruno Pedroni is a self-taught luthier whose path into violin making began with artistic drawing and a desire to explore materials. After his first years in lutherie, he met Francesco Bissolotti, who took him under his wing not for his technical skills, but for the spirit with which he approached the craft. They worked together for ten years, until Bissolotti’s passing.

Over the course of his life, Pedroni has built more than one hundred instruments — including cellos, violins, violas, double basses, and viola da gambas — alongside extensive restoration work. Today, he defines himself above all as a cello maker, pursuing a personal research focused on sound, material, and the individuality of each instrument.

1. What does it mean today, for you, to be a luthier?

Being a luthier means first of all learning how to deal with matter.

Wood comes first. One must always remember that an instrument is built with one primary purpose: it must sound.

Once standard parameters are set aside, the real task is to understand the material and draw out the best possible acoustic response from it. That is the true starting point.

2. Which aspect of your work best represents your professional identity?

In the collective imagination, the figure of the luthier is often overestimated. In the end, he is not an artist, but a craftsman.

For the first ten years, lutherie was secondary to my work as a landscape designer, practiced in my spare time. Only after retirement did I dedicate myself more fully to it.

Despite this, I have built 65 cellos, 25 violins, 20 violas, 5 double basses, and 2 viola da gambas, and carried out numerous restorations.

I believe lutherie is already full of books and talk. It is better to stay at the bench and build.

I identify myself as a cello maker: over time, I have designed and built 16 different cello models.

3. How do tradition and research coexist in your daily work?

With full respect for history, I have always tried to look beyond it, attempting to improve what can be improved.

All the movable parts of the instrument — endpins, endpin supports, tailpieces, soundposts, bridges — are my true passion. I believe I have helped bring greater awareness to the importance of these elements, which are often underestimated.

Over time, I have designed various cello models with different dimensions, respecting tradition without being enslaved by it.

4. What is the most important question a young luthier should ask at the beginning of their journey?

Today, a young luthier has no real choice: in order to survive, they must obey market rules.

Dealers have pushed lutherie into a funnel:

uniform varnish, identical models, same colors, same setups, same strings. The risk is ending up doing the exact same work for the next thirty years.

Lutherie has become merely an exercise in precision. The machine has taken over.

You cannot compete with CNC machines: once an instrument is dismantled and measured, a machine can produce fifty identical copies in a week.

The real question, then, is:

👉 Do I have something of my own to say?

Because only by focusing on the personality of the instrument, if one truly has the ability, can this spiral be escaped.

5. Looking ahead, what do you think will be the main challenge for contemporary lutherie?

The main challenge is to return to actually building, rather than pretending to do so.

To step back.

To stay at the bench — not at the bar across from the workshop.

The market has changed: today, very well-made white violins circulate at around €250, made with good wood.

To reverse the trend, it is necessary to create something that machines cannot do, restoring character to the instrument, without conforming to uniformity.

The Violin Post – Editorial Note

In an era where lutherie increasingly risks becoming a matter of replication, precision, and market conformity, voices like Bruno Pedroni’s remind us that craftsmanship is not defined by nostalgia, but by responsibility.

Responsibility toward material, sound, and the individuality of each instrument.

Beyond myths, beyond standardized models, this interview speaks to a form of violin making that resists simplification — one that accepts tradition as a foundation, not a constraint.

At a time when machines can reproduce forms with ease, the real challenge remains what cannot be replicated: judgment, experience, and the courage to make choices at the bench.